For this month, I wanted to talk about functions. It was a topic in my pedagogy class, I had to teach it to my algebra class, and it just kept appearing in places.

I didn’t know the actual definition of a function until I had to teach it. I guess along the way, I just internalized what it was without paying attention to the definition.

Before we can define a function, we have to define a relation. Suppose we have two bags of things, maybe one with names of our friends and the other with candy.

When we decide which name is paired with which candy (or candies), we’re assigning a relation on these two bags of things. Let’s say, I have three names: Aryo, Ben, and Chris and I have four types of candy: Kitkats, Gummies, Nerds, and M&Ms. One relation on these two collections (or sets) could be: Aryo is paired with Gummies, Ben with Kitkats and Nerds, and Chris with M&Ms.

The example relation above was completely arbitrary, but this freedom helps us define even more things. We are going to make another free choice: the names will be the input set while the candies will be the output set. This is to establish the relationship between the sets, which set is directly influencing the other set.

Think of this like the relationship between a dish that you buy at a restaurant and the price associated with that dish. The input set are the choices of food while the output set are the prices. (So, you’ll notice here that sometimes, two inputs can be paired with the same output. A burrito costs 7.99 while an enchilada with a taco also costs 7.99.)

WHOA! That means we can really just define whatever relation we want on any two collections, and you’re right! That’s the freedom the openness of definition gives us. But, to make it more useful and practical, we usually give more restrictions.

One restriction is what gets us to functions. A function is a relation such that each thing in the input set can only be paired with one thing in the output set.

To go back to the restaurant example, this means that you’ll never run into a dish costing two different prices! (Meal versus just the burger doesn’t count as one input, those are two different objects.) That would just be too confusing. To go back to the names and candy example, with our choice of what is the input and what is the output, do we have a function?

For my Intermediate Algebra class, I wrote up this sheet of notes that helps with identifying if a relation you're given is a function or not. It also gives a brief run through of the different forms of a function in this algebra class.

Now that you know the abstracted definition of what a function is, let’s dive into the difficult parts of learning it as an algebra student. Notation is such a difficult thing to introduce to students, especially when it doesn’t mix well with the previous structures we’ve had.

We spent days or even weeks talking about how “x” is the input while “y” is the output, and suddenly, we bring in this funky “f(x)” monster onto them and say it’s practically the output. In my pedagogy class, we read this paper “Why use f(x) when all we really mean is y?” by Patrick Thompson which highlights the main hurdle of introducing the “function” notation onto students.

To summarize Thompson, the introduction of the notation is usually unmotivated, why introduce something new when the “y thing” was working previously. Furthermore, the notation is usually misapplied as this “y=f(x)=mx+b” string of symbols which puts a lot of confusion on what it means to be equal to something.

My main takeaway (and how I introduced it in my class) is getting rid of ambiguity. Remember when I made the arbitrary choice of making names for the input? In the slope-intercept form of the equation of the line, y=mx+b, we made the arbitrary choice of making x the input because of tradition. I could have made the other choice of making m or b the input! So, the use of “f(x)” makes the world know that x is the input in this equation, while m and b are just hanging around for the ride.

One thing that I hate about this notation is how we use parenthesis. We have made students comfortable with omitting the multiplication sign when we use parenthesis, such as 2(3+5) really means 2 times (3+5). So, when we introduce this f(x) notation, you’re bound to get someone asking if this means f times x and it is a valid question and confusion. Unfortunately, we live in traditional times and we just accept the circumstances. The answer usually being “it’s just how it’s been”.

(Truth be told, there are way more things to talk about in this realm, but I think I'll save more discussion for another month.)

Let’s talk about function transformations. These actions can be an extension of our f(x) notation. Some examples are:

As a counselor (tutor) for the Math Resource Center here at UNL, I have the chance to be met with questions that I might not be prepared to help with. One such question from a College Algebra student was something like: “If I know (1,6) is on my function f(x), what other point do I know for the function af(kx-m)+b?”

Now, I’m a helper, and I have a massive pride in being able to help students no matter what, so I wasn’t going to back down from this problem. In hindsight, I should have passed the baton to a more fitting counselor who was actually teaching that class and that topic. But, I tried my best and worked with the students to go over what it means to apply those transformations. I got the question wrong. A hint pops up saying something along the lines of “Remember that inside the function, the order of operations are reversed” or that the effects of the changes are opposite of what you’d normally think. It clicked!

I say this story, not really to enlighten you better on how to do function transformations, but to highlight that even in grad school, you’re always going to be faced with a challenge related to functions. It is a difficult topic and to connect it back to August’s Monthly Math-y, I am admitting that this is hard, but it won’t stay that way forever. I know how to deal with function transformations now, it took a while, but I got it.

To conclude our icebreaker of a discussion (there’s more to talk about with this topic), I wanted to give motivation why understanding functions matter, extending outside of math.

For the computer scientists and the programmers out there, functions are integral in being able to do what you do. That part of your code that says “int sum(a,b)” is the CS way of using functions. The input being a and b, while the output being that “sum(a,b)” that gets a specified name tag for integer. It took me years to realize that functions in math are basically the same thing as functions in CS.

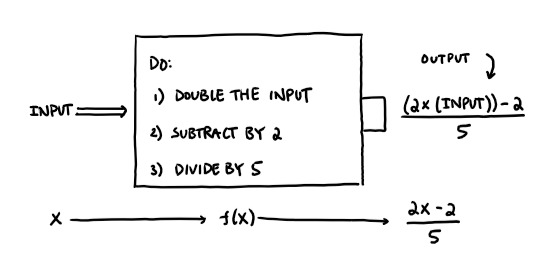

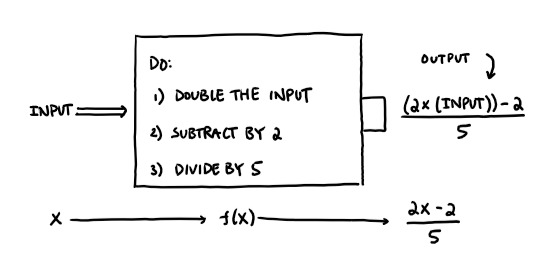

You take input (either x or maybe a whole class object), you do some magic (square the number or maybe change the value of some aspect), and you give something back. The whole “function machine” way of introducing this topic that I didn’t use, but maybe should have.

For the “real worlders” out there, go back to the restaurant example that I mentioned at the beginning. This idea really does seep into the logic and structure of a lot of things in life. When you notice relationships between a cause and an effect, you’re noticing a function between an input and an output. For example, the hours you work paired with the amount of money you receive at the end of the pay period. Some of you may not even think about math consciously, but it is there.

Another way to see it is through your smartphone, it may not seem like it, but these are function machines that have thousands of invisible functions within them. Taking a photo, blasting music, sharing a post, or tweeting, these are all working with an input-output relationship. It may not really seem all that important since relation and function have such an open, freeing definition, but that’s exactly why it’s present everywhere. Hopefully, I’ve given you a bit more of an appreciation for this little scary, not-so-scary topic of math.

Uploaded 2021 November 28. This is a part of a monthly project which you can read about here.